Innovation Meets Experience

In January of this year a gentleman who has a granddaughter with Rett Syndrome introduced me to his neighbor, David Scheer, a 31-year veteran of the life sciences industry. I was eager to meet David, whose entrepreneurial focus lies at the intersection of finance and science. Our planned hour of conversation turned into a three-hour discussion as we delved into David’s network, experiences, and the potential synergies we might explore. Over the past 9 months I’ve come to rely on David’s insights, perspective and advice. I’m delighted that he has agreed to serve on RSRT’s Professional Advisory Council and look forward to working closely with him on our drug development strategies.

MC: David, please start us off by telling us a bit about your background.

DS: I began with an undergraduate degree in biochemical sciences from Harvard and went on to study cell and molecular biology and pharmacology at Yale. While in graduate school during the early 80’s, I started doing consulting work in the emergent fields of molecular biology and biotechnology. This became a life sciences consulting practice that brought together venture capital, transactional advisory services, and corporate strategy. Scheer & Company is best known for having launched a series of companies spanning the fields of infectious disease, cardiology, oncology, and neurology, to name a few. We’ve had some pretty significant successes among the entrepreneurial enterprises we have launched and built. One of our companies launched a product that was ultimately acquired by Johnson & Johnson; another, a company called Esperion Therapeutics, developed a product in HDL (good cholesterol) therapeutics which was sold to Pfizer in 2004 for $1.3 billion. In the roles of founder and director of numerous companies, I have been involved in identifying technology, recruiting people and raising capital. In most of my more recent companies, I have served as Chairman of the Board.

MC: David, one of your companies, Aegerion Pharmaceutical, operates in the ultra-orphan disease world. Can you tell us a bit about that company?

DS: Aegerion has developed a drug for a very rare disease present in only one in a million people: Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia (HoFH). The disease causes very high bad cholesterol that confers high risk for cardiac events like strokes or heart attacks, even in individuals as young as teenagers, for those who are untreated. We are pursuing approval with both FDA and European regulatory authorities, and we have put in place management and commercial infrastructures in the US and Europe to make the drug available to patients in need, when there is the proverbial regulatory green light. As Chairman of the Board of this company, I have become quite interested in the area of rare diseases.

MC: Lately, pharmaceutical companies seem to all be starting rare disease initiatives. This is in stark contrast to the traditional focus on blockbuster and “me-too” drugs. What is driving this change?

DS: The traditional view has been if there are not enough patients, it’s not really worth developing a drug. However, pioneering companies such as Genzyme, BioMarin, and more recently, Alexion, have successfully developed life-saving drugs to treat rare diseases while providing a return on investment for their shareholders. In so doing, they have opened the eyes of people in the pharmaceutical industry. This shift holds clear potential for organizations working toward the development of therapies for rare diseases, such as the Rett Syndrome Research Trust.

I suspect that rare diseases may also provide an easier path for drug approval. Much of the cost of drug development comes at the end, during the extremely large and expensive clinical trials that are needed for blockbuster drugs. In the rare-disease space, due to the small population sizes, trials will be much smaller, and therefore less expensive. Also, the regulatory process may be fast-tracked for a rare disease, as the FDA recognizes the enormous unmet need and cooperates with sponsors and patient advocates to provide new agents sooner.

So interest in innovation in the rare disease category has turned bullish, which makes this an exciting time for someone engaged in your work, Monica, and frankly also for people like me who are really interested in efficient and effective development of new drugs.

MC: Are large pharmaceutical companies set up to tackle drug development for rare diseases?

DS: I think the answer depends on the drug company. The bulk of the rare-disease experience in drug development has traditionally come from innovative smaller companies. For example, Genzyme, which started off as an idea on the back of an envelope, became a multimillion-dollar pharmaceutical company with a large number of products in its portfolio, and was recently acquired by Sanofi-Aventis. Sanofi now has a franchise that is very capable and active in the rare-disease field. Other companies have either built from scratch, made smaller acquisitions, or are making partnerships or deals with companies that have assets or programs in rare-disease drug development. Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline have done this, and both now have rare-disease units.

I think it is too early to predict the success of these larger companies. Can the big companies be as effective as some of the smaller companies have been? Will the entrepreneurial spirit of a Genzyme in the early days be retained or lost as part of a larger company? We shall see.

MC: How do FDA drug reviews for a rare disease differ from those for a common one?

DS: The FDA has really had to modify its approaches to adapt to the needs of the rare-disease community. In fact, there is an orphan-disease unit within the FDA that is specifically tasked to review rare-disease drugs. These people are very familiar with how to evaluate a drug through a very different lens than is ordinarily used. It is important to keep in mind that regulatory decisions are always based on a favorable risk-benefit relationship.

MC: The Rett community, including families, clinicians and researchers, is highly concerned----and properly so---with rigorous validation of pre-clinical advances and the complexities of developing solid protocols for outcome measures. Though Rett patients are a small population, the range of symptoms is staggering, so there are many issues to address.

DS: There are no perfect drugs – even Tylenol can have dreadful side effects if taken in excess, such as liver failure. The FDA must balance the solemn task of making available new and important therapies, while ensuring that such agents demonstrate safety and efficacy commensurate with the condition being treated.

MC: You were only recently introduced to Rett. What have you found most interesting thus far?

DS: That it has attracted some very talented individuals. The scientists, thought-leaders, and patient advocates involved in Rett Syndrome research represent an incredibly impressive group. Perhaps this is because Rett Syndrome is believed to be scientifically very tractable. It certainly helps that it is a single-gene disorder. The number of chronic conditions that can be attributed to a single gene is relatively low. So if I may say this, those in need of therapeutics for Rett Syndrome, may be fortunate in that there is an important foundation for discovery of potentially novel, disease-modifying therapeutics.

MC: I think the 2007 proof-of-concept reversal has also helped put Rett on the map; it had been a much more obscure disorder before that breakthrough.

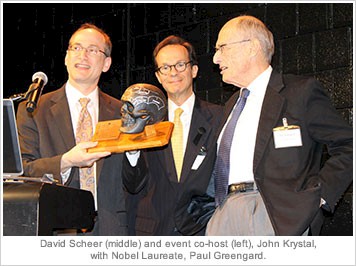

DS: I agree. Each year in my not-for-profit work, I organize and chair a conference in New Haven, in conjunction with Yale and the Long Wharf Theater, called Global Health and the Arts,. For the past four years, this conference has promoted examination of important disease topics in public health and global health. This past May, we explored the neuropsychiatric disease arena. We had a major scientific symposium, with some of the most well known academic and industrial thought leaders from around the world, who were able to give us an update on relevant areas of science and technology, drug development, genetics, genomics, and translational medicine. In the middle of this event we actually had several individuals comment on the importance of the work being done in Rett and related disorders.

DS: I agree. Each year in my not-for-profit work, I organize and chair a conference in New Haven, in conjunction with Yale and the Long Wharf Theater, called Global Health and the Arts,. For the past four years, this conference has promoted examination of important disease topics in public health and global health. This past May, we explored the neuropsychiatric disease arena. We had a major scientific symposium, with some of the most well known academic and industrial thought leaders from around the world, who were able to give us an update on relevant areas of science and technology, drug development, genetics, genomics, and translational medicine. In the middle of this event we actually had several individuals comment on the importance of the work being done in Rett and related disorders.

Monica, you need to continue doing what you do so well: ensure you have the best information from scientists at the cutting edge of this field, and then position that knowledge in a way it can be most effectively translatable. The more quickly drug development gurus can bring their expertise to the table, the better the chances of a successful outcome. I am very much looking forward to help you achieve that success.

Monica, you need to continue doing what you do so well: ensure you have the best information from scientists at the cutting edge of this field, and then position that knowledge in a way it can be most effectively translatable. The more quickly drug development gurus can bring their expertise to the table, the better the chances of a successful outcome. I am very much looking forward to help you achieve that success.

MC: Thank you, David, and on behalf of every Rett family, welcome.